|

This is article Number Three in what I am tempted to call “why do people do what they do and what would it take to make them re-evaluate what they are focusing their energy on?”

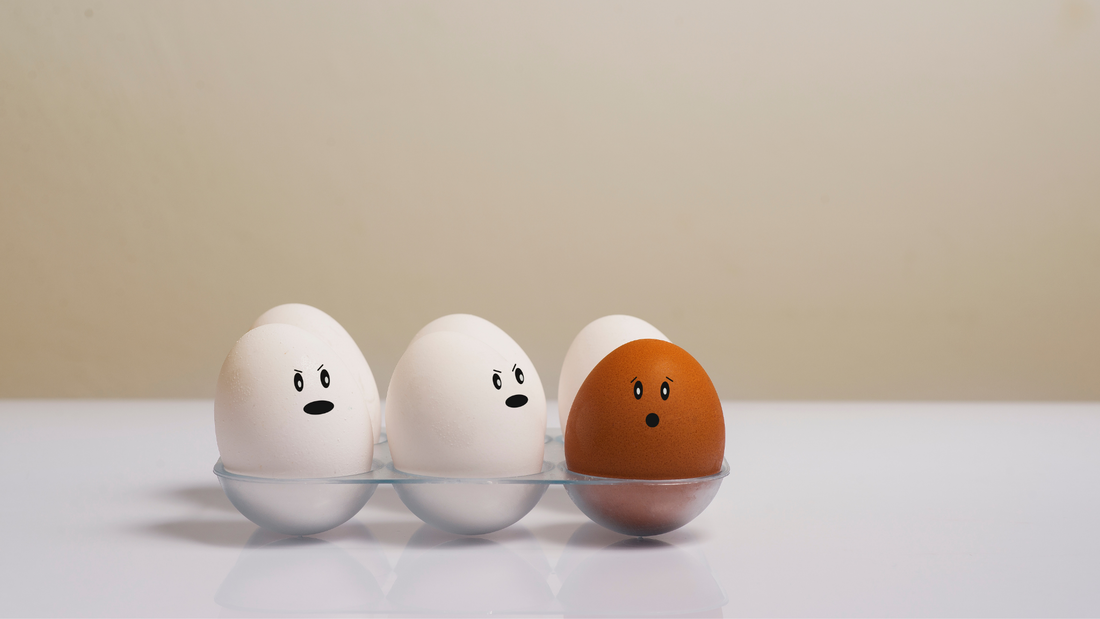

So, today, I would like to ask you… do you have Stockholm Syndrome for capitalism? First of all, don’t get triggered by my use of the C-word. This isn’t going to be a Trotskyite polemic about the power of the workers and the oppression of the bourgeoisie. Unless you are reading this in North Korea – and I am fairly certain you’re not – I think we can all agree that we all are operating under an economic and political system that has held sway over people’s lives in one form or another since the fifteenth century. I am going to suggest that it has changed the way that people think, operate and interact, and has permeated many life and lifestyle choices that influence you and the way you run your business. But, as we are very fond of pointing out, “just because it is, doesn’t mean it has to be.” Now that I have hopefully stopped some of you from foaming at the mouth in fear of me wiping the value off your share portfolio, I should explain Stockholm Syndrome. It was coined in 1973 after a botched bank raid in… guess where… yep, that’s right… Stockholm when, over the course of a six-day stand-off the hostages that had been taken developed a close bond with their captors, to the point that they became concerned for their welfare. My suggestion is that many of you, reading this at work, while you perform the tasks that you need to do to live, might, possibly, be in a similar situation. I’m not suggesting that you are being held against your will, but I contend that you might be making excuses for what you do and how you justify it that are, well… curious… and deeply ingrained. I suspect that the beliefs wrapped up in them may be affecting how you interact with your teams. And if there’s one thing that we want to do, it’s to make teams feel more valued, more listened to, more seen – and perhaps the dominant force behind all of our lives has a bearing on things in ways that you might never have considered. Let’s have a quick crash through western European history seen through the lens of the United Kingdom. I apologise for being so UK-centric here, but It’s what I know. I would love to hear how things developed in other countries, and to hear the differences and similarities. It’s rough, but here are the broad strokes. A long time ago people worked in small, self-supporting communities, based on agriculture and predominantly organised into small settlements. The community worked to produce what it needed to live, with any surpluses being used to buy things that the community could not produce for itself. As farming techniques improved fewer people were needed to work the land and this freed people up to provide ancillary occupations and services. People could move from just surviving, to creating things. Having things became a measure of how successful you were. Bigger house, nicer clothes, better food. It was always thus, but with the rise of a powerful mercantile class in the sixteenth century the marks of success became more apparent and extreme and made status symbols open to people other than monarchs and the nobility. As the Industrial Revolution increased the ability to create a wider range of products and the number of roles that began to make up increasingly urban societies grew, so people stratified along layers that were defined by what they had acquired through their roles. Fast forward this to the 1970s and 1980s. By this time, in the UK, success had become delineated by home ownership, the car you drove and where you went on holiday. Increasingly it became necessary for households to have two incomes to support these important badges of lifestyle. At this point I should pause and emphasise that I am not advocating a gendered split in work-work and home-work. I don’t care who does what – all I am pointing out is that one income became increasingly insufficient to keep-up-with-the-Joneses. So far, so what? People want nice things and they are prepared to work for them. What’s wrong with that? Nothing, but look at what develops beyond that if you pause and consider what this entails. In a previous “what the hell?” post I questioned the chimera of measuring Employee Engagement and how that wiggly line of how much people like their work bumbles along at 70-80%. People want to be somewhere else at least some of the time while they’re at work. I’ve also considered how businesses occasionally try to infer a familial bond with their employees to ameliorate the time they spend away from their real families. Both of these factors could be seen as manifestations of a desire to mask that very human trait of work-as-necessary-chore. Generally speaking, if they didn’t need the money, people would rather not be at work than be at work. To make up for this people reward themselves with things that they can only get by putting up with work. New clothes, new gadgets, holidays… the list goes on. Ask yourself… how much do you look forward to and enjoy your weekends? (The weekend of course, like the beginning of the four-day working week, is a relatively recent development, so things can, and do change if you question the logic that claims to underpin the behemoth that is The Way Things Are.) How much do you look forward to Monday and getting back to work? But there’s more to it than an exchange of time and freedom for money to buy things, hence my contention that many make excuses for the thing that holds them in its grasp. As an example, I give you the personalised number plate. Once I point this out you won’t be able to stop seeing it. (That’s called The Baader-Meinhof Effect if you’re interested… but more of that another day.) Next time you are out and about, just check out how many people are driving very expensive new cars with personalised number plates. Aside from the environmentally damaging and toxic desire to demonstrate how well you are doing by driving the latest car or rocking the newest model of mobile phone, at what point did it not become enough to drive a car that costs more than some people’s homes? I can only conclude that by shelling out several thousand pounds on a registration plate that contains your initials, or a reference to your name, on top of your top-of-the-range Range Rover, you are wanting to show that “you are winning at capitalism.” I can almost feel the furious typing that is going on from some quarters right now, defending their choices and explaining why they have done it. But isn’t that the essence of Stockholm Syndrome? Defending the thing that has imprisoned you? I could go further. I live in the sixth richest country in the world. We have homeless people and food banks and children who don’t have enough to eat. We also have people living in vastly over-priced houses and individuals and organisations that try to game the system any way they can to reduce the taxes they have to pay. In between those extremes we have a great swathe of the population who could do something about it, but won’t… because, because, because. Because they might have to give something up. Because they’ve worked hard for it. Because why should I, nobody else will. Despite what I said earlier, this does sound like I am calling for you to join me on the barricades. I’m not. I’m just putting it out there for debate. As an unanswered question if you like. Why are you doing what you are doing is one aspect of it, but for me, the more important aspect of it is “what are you expecting other people – in your workplace, in your teams, amongst your stakeholders – to do so we can all keep playing this game?” As with much of the work that we do with teams, it’s only by asking the questions that challenge the accepted norms that you can create something different. Perhaps asking a big question like this will give you pause for thought. Now, get back to work. Someone else might be winning.

0 Comments

|

AuthorColour; Noun (Vicky Holding and Howard Karloff) Archives

November 2022

Categories |